August 9, 2021 by Passiflora

The Human and Inhuman Nature of Plants: Part 1 — Introduction

When it comes to plants, it’s easy to think of them as inanimate objects; however, this could not be any further than the truth. Plants are dynamic, living, breathing organisms that are constantly observing their surroundings and using this information to adjust how they’re growing. I’d like to discuss in what will likely be several overarching posts the dynamic life of plants and I hope that in doing so you will walk away with a little more appreciation for our (usually) photosynthetic friends.

To really get a grasp on the sheer wonder that is plants, there are two key points that I need to introduce to you first. The first deals with what makes them so strikingly different from us and another that makes them extremely similar. When it comes to plants, they have a decentralized body plan. In humans, we have a heart that moves blood throughout our body and it works pretty great our entire lives. We have a single central nervous system for processing the information around us, and other organs with specific functions. If I remove a person’s heart they will more than likely die. Same with the brain or lungs. Plants, however, have no such centralized organs. I cannot try to take the lungs from a plant or the brain from it. The roles of these organs (heart, lungs, brain, etc.) are instead dispersed throughout their body in various specialized tissues. This does not mean, however, that the roles of these organs in humans are not also completed by tissues in plants. This is incredibly important for a plant because unlike most animals, should a predator appear, they cannot simply run away (more on this later though). Instead, by decentralizing their bodily tissues so various tissues throughout their bodies complete these roles when a predator inevitably shows up and destroys a large chunk of the plant, the rest of the plant can simply take on the additional work. This aspect of life for plants simply cannot be understated in importance for what plants are and how they function. By having tissues dispersed throughout their bodies completing these roles it is sometimes easier to think of a plant not as a single organism, rather, to consider it like a community of individual parts in constant communication that are all working together to complete desired goals (more on this later, too!).

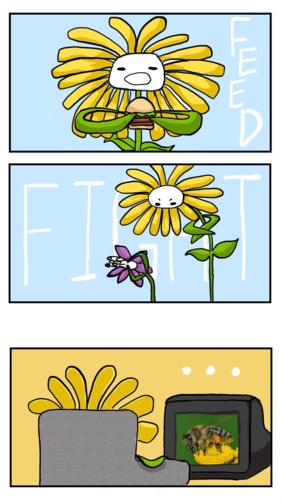

After mulling that over, I’d like to now flip the script and briefly talk about what plants share with us. It’s easy to look at a plant as being barely even living (in fact I have heard people say “it’s almost like they’re alive” in discussing plants), so much so that there’s an unofficial term for it — plant blindness. Plant blindness is considered a cognitive bias to ignore plants in our surroundings as our brains are wired to look for movement in animals, to look for patterns in our environment, or find faces. We evolved to watch out for predators in the grass after all, not to watch out for the grass itself. This doesn’t invalidate the “alive-ness” of the grass, it’s just a bias we need to account for in ourselves. What plants share with animals, with us as well, is they are living organisms on this earth. That seems like a straightforward enough statement doesn’t it? But in that, I mean they must achieve the same successes in Darwin’s three “f"s that all animals face. As one of my favorite profs put it, they need to fight, to feed, and to fornicate (have to keep it PG after all). These seem pretty easy to imagine in the animal world, for the most part, however plants have evolved some stunning, fantastic, or downright awe-inspiring ways in which they fight, feed, or fornicate.

Given their different body plans and immobile lifestyles (though I’m sedentary enough to give them a run for their money), the ways plants have evolved can be otherworldly or seemingly too human. For us humans, and a large amount of the animal kingdom, we’ve developed different senses to achieve these three “f"s. There’s the ones you’ve learned in school (taste, touch, smell, sight, hearing) and a good many more things considered senses, such as proprioception. Proprioception is our sense of vertical orientation (balance) and the innate knowledge of where our limbs are relative to one another. Imagine how difficult day to day activities like walking would be without this sense (this is a major hurdle for robotics engineers). These senses seem unique to animals don’t they? Well, you are correct; however, you’re also wrong.

You’d be correct in thinking that way, though not for the reasons you’re likely to expect. How these senses are defined ties organs to their function. Sight, for example, is the product of photoreceptors in the eyes sensing light and sending these signals to the brain. This is a bit of a problem because that means that other forms of life don’t have a sense of “sight” unless they also have eyes and a brain regardless of how sensitive they are to light. Keep that point in mind because I’ll frequently just use the senses when I explain their parallels in plants. I don’t want to anthropomorphize plants, if anything my goal is to divorce things we consider human from what actually makes us human (that is important because people like to think in dichotomies so when we think humans do it, we fall into thinking other living things don’t.) I am lazy and writing “a plant sees…” is a lot easier than “a plant’s light sensitivity results in a growth response to…”

You’d be incorrect in thinking these senses or at least the pattern of sensing changes in the environment or one’s self and then responding to them (see why it’s easier to just say sense?), are unique to animals. It may even be disconcerting to consider that other living things, even plants, share all these “senses” with us. That is because humans have a cognitive bias to consider ourselves and our species to be unique and special, and through that you’ve equated these senses with being human. To understand how plants achieve Darwin’s three “f"s we first need to understand how plants sense the world around them and these senses are frequently diffused throughout their body, rather than in specialized organs like us.

This may feel like you’ve entered a bizarre world but the rabbit hole only gets deeper. So let’s take the plunge.